Understanding is key to maintaining good bone health.

“Studies have consistently shown that patients often lack knowledge about the risk of cancer treatment-induced bone loss and means for prevention and treatment."

Gradual bone loss is common with aging for both men and women, though women tend to have a younger onset of bone loss compared with men. It is also true that genetics and hormones play a role in bone health. Optimal bone health involves two levels of regulation. Hormonal influence (e.g., androgens, estrogens, calcitonin, and parathyroid hormone) and the mechanical forces imposed by gravity combine to form one level of regulation. The other level of regulation is the dynamic balance between osteoblasts, which are cells that lay down new bone, and osteoclasts, which are responsible for the breakdown and assimilation of old bone. The balance between osteoblast and osteoclast functions regulates bone health and maintains physiological equilibrium.

Cancer affects both generalized and local bone loss.

When it comes to cancer, nearly all cancers can have significant negative effects on the skeleton and are a result of multiple, complex-related factors. These include both the direct effects of cancer cells and the effects of treatment, including chemotherapy, corticosteroids, and androgen deprivation therapy. Further, the skeleton is a common site of metastatic disease, especially in prostate cancer, as cancer cells growing within bone induce osteoblasts and osteoclasts to produce factors that stimulate further cancer growth.

Baseline osteopenia, or osteoporosis, is a significant risk factor for patients diagnosed with prostate cancer.

In men, osteoporosis is strongly associated with aging, affecting at least 10% to 25% of men who are 60 years of age or older. Because osteoporosis is often underdiagnosed in men, the actual numbers may be much higher. Additional risk factors for osteoporosis include smoking, a substantial loss of height since young adulthood, a recent personal history of a fall or fracture, low protein intake, and a family history of osteoporosis.

Newer treatment options for prostate cancer have changed the landscape of treatment, with significant improvements in cancer survivorship. This takes into account the optimal management of skeletal health and the care provided to prostate cancer patients in this regard.

Bones are affected by prostate cancer itself and also by hormonal treatment, which is the dominant type of treatment for prostate cancer.

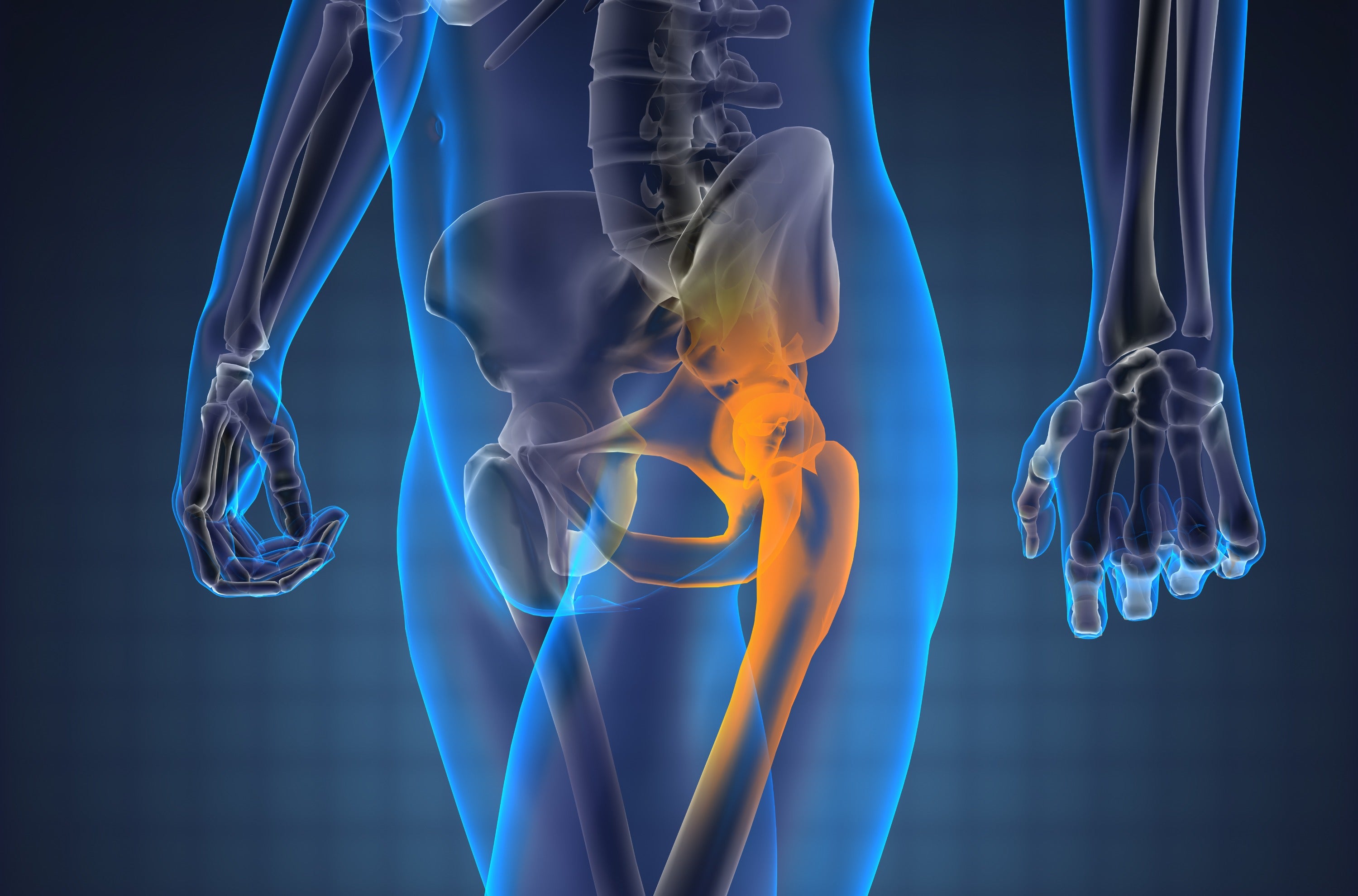

In prostate cancer, metastases preferentially develop in the bones of the axial skeleton (made up of the bones in your head, neck, spine, hips, and ribs), where red marrow is most abundant. The bone metastases in males with prostate cancer are usually osteoblastic (i.e., characterized by new bone formation). Although these blastic areas are harder, the structure of the bone is not normal, and these areas actually break more easily than normal bone. More than 60% of men with advanced prostate cancer will eventually develop bone metastases. Bone metastases increase the risk of fracture and other skeletal-related events, such as spinal cord compression or paralysis, or needing surgery or radiation for bone pain.

Apart from metastases to the bones, hormonal treatment for prostate cancer also negatively affects the bones. The main androgens in the body are testosterone and dihydrotestosterone (DHT). Most androgens are made by the testicles, but the adrenal glands (glands that sit above your kidneys), as well as the prostate cancer cells themselves, can also make androgens. Because testosterone serves as the main fuel for prostate cancer cell growth, it is a common target for treatment. Hormone therapy (also called androgen deprivation therapy, or ADT) is part of the standard of care for advanced and metastatic prostate cancer. ADT is designed to either stop testosterone from being produced or to directly block it from acting on prostate cancer cells.

The efficacy of ADT is based on its reduction of serum testosterone to near-castration levels. Unfortunately, this has significant negative implications for bone health. Systemic glucocorticoids are essential to offset the toxicities of certain prostate cancer treatments, such as docetaxel, cabazitaxel, and abiraterone acetate, that are used in castration-resistant prostate cancers. However, these drugs also adversely affect bone health through their effects on cells involved in bone turnover.

“If you are receiving ADT, there are a number of things you can do to reduce your risk of bone loss. Make sure you are not leading a sedentary lifestyle—exercise regularly and keep fit with weight-bearing activities like walking. Avoid smoking and excessive amounts of alcohol. Supplement your diet with vitamin D and calcium to keep bones strong.”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/healthy-living/urologyhealth-extra/magazine- archives/winter-2014/keeping-your-bones-strong-during-prostate-cancer-treatment

Understanding the larger implications of weakened bone health, especially for the activities of daily living, is important for the patient and the caregiver. While life expectancy has improved due to advances in treatment, maintaining a good quality of life, including the ability to work and preventing fractures, is part of optimal survivorship. The next blog will address ways to advocate for your bone health, including prevention and treatment options.